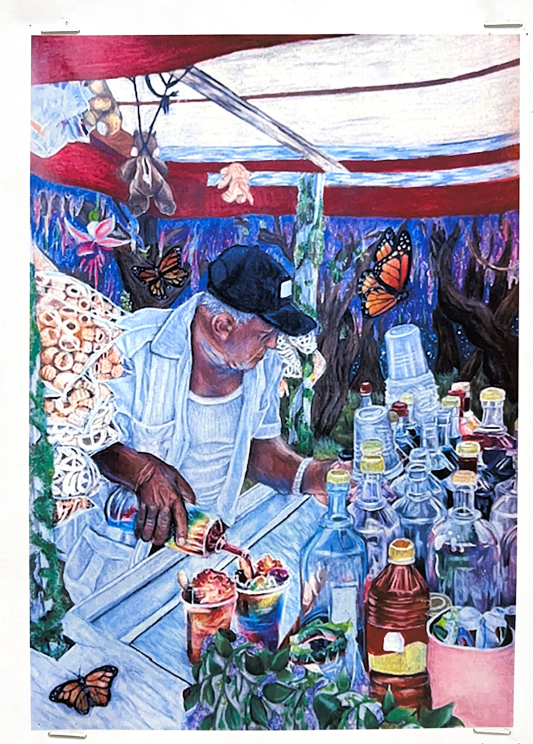

Uprising (2024) is a gripping film that takes us on an emotional rollercoaster, telling the story of two childhood friends—one a master, the other a servant—who reunite after a devastating war but as bitter enemies, each aligned with opposing causes. Set during the Joseon Dynasty, the film’s backdrop provides insight into societal structures, loyalty, and shifting power dynamics amid social unrest. Directed by Kim Sang Man, the film uses nuanced storytelling to explore personal identity, class, and moral conflict. The analysis will show that the characters’ lives reflect both the weight of historical events and the psychological torment of loyalty and guilt, while the class struggle is ever present in the narrative. Through these perspectives, Uprising offers insight into how the past shapes personal choices and the inevitable tensions between the privileged and the oppressed.

From a cultural historicist perspective, Uprising draws heavily on the historical context of the Joseon Dynasty, using it to highlight the shifting roles between the two protagonists. The period’s rigid class system, with masters and servants bound by Confucian ideals, is central to understanding the relationship between the two friends. The post war setting introduces social upheaval, with once immutable roles inverted as the servant rises to power, now leading a rebellion. A key scene illustrating this inversion occurs when the former servant, now a general in the rebel forces, confronts his former master, asking, “Do you remember the days when you thought I had no name?” The line speaks to centuries of systemic inequality. The servant’s rebellion is not just personal but reflects a broader rejection of a classist structure.

Through a psychoanalytic moral lens, the film delves into the inner torment of both characters, particularly the former master, who is plagued by guilt and a crisis of identity. Raised with the belief that loyalty flows in one direction—from servant to master—he now faces the consequences of that imbalance. His inability to save their friendship reflects his internal struggle, as his sense of superiority clashes with moral questions about justice, loyalty, and betrayal. The moral dimension intensifies in a scene where the former master hesitates to kill his childhood friend in battle. This moment illustrates his subconscious desire for redemption—seeking to reconnect with his past self, who knew friendship without the barriers of class. The former servant, however, interprets this hesitation as weakness, embodying the belief that morality has no place in revolution, where victory demands ruthless choices.

By examining Uprising through these perspectives, we gain a deeper understanding of how history, personal identity, and social structures are interconnected. The film serves as both a personal tragedy and a social critique, showing that reconciliation is often impossible when societal forces are at play. Uprising invites viewers to reflect on how historical injustices continue to shape the present, challenging us to reconsider the nature of loyalty, power, and the quest for justice in our own time